Agroecology & Revolutionary Politics

The interdependence of food security,

ecological agriculture & revolutionary Marxism

By Jack E. and T. Stearnes

The thing about agriculture is it’s the most important thing we do, and we are rapidly approaching a point where capitalist agriculture will not be able to feed the global population (if it can even be said to do so in the first place).

At the same time, there’s a huge amount of bad information out there regarding “sustainable” agriculture, specifically in a left-wing context. Many otherwise well-meaning lefties will nod at poorly defined systems like permaculture when discussing ecological communism. Systems like this cannot meet the needs of a globalized world, especially when we need to maintain cereal grain production as a caloric base.

One of the better approaches to sustainable agriculture is the field of agroecology, which is well-suited to systems theory and emancipatory, left-wing politics. In fact, there is a necessary and reciprocal relationship between the creation of a classless society and ecological agriculture; you cannot have one without the other. Many agroecological studies overlook that producing food sustainably would require communal property relations. Likewise, many communists overlook the necessity of studying agricultural systems and their potential implementation in both the revolutionary and post-revolutionary periods.

With this in mind, what we’ll try and do in this essay is the following:

- set a definition for what it is we mean when we talk about agriculture,

- give ourselves a baseline understanding of the problems of capitalist agriculture, including how we got to this point,

- merge a number of agroecological approaches to the subject to give us a picture of what truly ecological communist agriculture would look like, and

- use these ideas as a polestar for socialism, both in its functioning as a social system and our strategy to get there.

Agriculture Defined

When we think of agriculture today, we might think of the proud, lone farmer, perhaps somewhere in the American Midwest, sitting in their combine listening to Johnny Cash or some other flag waving sellout as the sun goes down on another day of good, honest work. If we’re more honest with ourselves, we might picture poorly paid, immigrant laborers working half-hunched over in blistering heat to harvest strawberries and watermelons. But both portraits miss the broader reality of modern agriculture. When conceived of as a system, it’s difficult to define where it begins and where it ends. What about the engineers and factory workers producing synthetic fertilizers? Or the truck drivers transporting produce to supermarket shelves or the cooks turning this produce into edible food? Where do they fit in?

If we define agriculture as simply those activities and processes that take place on farm, whether it be growing and harvesting cereal grains, fruit and vegetables, or raising livestock, we lose sight of the broader systems that “agriculture” as such relies on, and that rely on it. In order to really conceptualize sustainable agriculture, we must think systemically. Defined this way, agriculture necessarily includes pre-farm systems such as the production of seeds, fertilizers and farm equipment, as well as post-farm systems including packaging, preservation, transportation, cooking and even consumption. If we’re setting as our goal an understanding what’s necessary for a theory of planning for sustainable agriculture, our approach needs to take into account the series of systemic recursions that what we call “agriculture” fits into.

So where to begin with a theory of classless, sustainable agriculture?

For our purposes here, we’ll define agriculture as the processes directly related to the production and consumption of food. If we were to broaden this definition, we would wind up with a sprawling essay discussing the best ways to produce energy sustainably or even the economic laws of a communist society, which, while necessary for the functioning of any sustainable, communist agricultural system, will be outside the purview of this essay.

Agriculture Today

In the same way that an understanding of the laws of capitalist society is necessary to understand what must be superseded in communism, it’s also necessary to understand capitalist agriculture in order to understand what would make communist agriculture truly sustainable.

Capitalism was considered historically progressive because it socialized production. It took a series of solitary producers with minimal connection to each other and created a global system in which production became a collective endeavor. Or, at least, that’s how it’s supposed to work. Capitalism operates as a series of independent firms producing competitively for the purpose of exchange. Because of this, we all rely on each other to produce what we need to survive and thrive. This socialized production, however, is in direct contradiction with its competitive nature. It is socialized, yet chaotic. Uncontrolled and out of control. This is clearly the case when it comes to capitalist agriculture, where production takes place in a highly specialized fashion with all of its parts increasingly decoupled from, and in contradiction to, each other.

This competitive, exchange-based economy ensures that, agriculturally, we produce what is profitable, not what is needed for a healthy society nor even a society that maintains its ability to continue to produce food. This is the classic exchange value vs use value contradiction at the core of capitalist society. As we’ll see, applying the principles of a competitive, exchange-based economy to agriculture was initially both possible and highly profitable, thanks to a series of productivity gains. However, many of these gains relied on an appropriation of the ecological surplus – a surplus that is rapidly being depleted.

How We Got Here

The history of modern capitalist agriculture is the story of humanity’s changing relationship with our broader ecology. Let’s take a step back in history to understand how we arrived where we are now.

To give ourselves an abstracted view of (mainly Western) European feudalism as a coherent system, we can see that it differed from capitalism in that instead of placing emphasis on the productivity of labor, feudalism was more concerned with the productivity of land.1 Those with enough political clout – lords, barons, queens, kings, etc. – extracted rents from the producing class – the peasantry – who were tied to the means of production – the farmland – in a legal relationship that bonded them to a specific place for their whole lives. The farmland the peasants occupied was legally controlled by the political rulers of a given area, and this political coercion over the producing class to give up portions of their surplus was exercised over both manorial domains held outright by the ruling class and the tracts cultivated by the peasantry.

It was this situation, peasants working land for both themselves and the ruling class, that led to the development of the highest stages of feudalism and its ultimate terminal crisis. The feudal ruling class tended to take the best tracts of farmland for themselves, and had an interest in improving the land insofar as they were always interested in maximizing harvests. Peasants, on the other hand, necessarily sought to maximize the productivity of their “own” land (to lessen the burden of the demands of the ruling classes) both through reclaiming “natural” and unworked soil and through developments in various agricultural processes. And it is because of this tension that though we tend to think of feudalism as a zero-growth static system, this was, of course, not the case. Technical developments, while nowhere close to as common as in capitalism, did take place with the adoption of iron plows, new systems for soil management such as the field rotations and, crucially, massive land reclamation projects. The ecological impact of these land reclamation projects should be obvious, and can be noted in the historical record in instances such as the slow loss of old growth forests.

This socially driven ecological crisis was at the very least partly to blame for the crisis of late feudalism. As stated by Perry Anderson,

The deepest determinant of this general crisis probably lay, however, in a ‘seizure’ of the mechanisms of reproduction of the system at a barrier point of its ultimate capacities. In particular, it seems clear that the basic motor of rural reclamation, which had driven the whole feudal economy forwards for three centuries, eventually over-reached the objective limits of both terrain and social structure. Population continued to grow while yields fell on the marginal lands still available for conversion at the existing levels of technique, and soil deteriorated through haste or misuse. The last reserves of newly reclaimed land were usually of poor quality, wet or thin soil that was more difficult to farm, and on which inferior crops such as oats were sown. The oldest lands under plough were, on the other hand, liable to age and decline from the very antiquity of their cultivation. The advance of cereal acreage, moreover, had frequently been achieved at the cost of a diminution of grazing-ground: animal husbandry consequently suffered, and with it the supply of manure for arable farming itself. Thus the very progress of mediaeval agriculture now incurred its own penalties. Clearance of forests and wastelands had not been accompanied by comparable care in conservation: there was little application of fertilizers at the best of times, so that the top soil was often quickly exhausted; floods and dust-storms became more frequent. Moreover, the diversification of the European feudal economy with the growth of international trade had led in some regions to a decrease of corn output at the expense of other branches of agriculture (vines, flax, wool or stock-breeding), and hence to increased import dependence, and its attendant dangers.2 (emphasis ours)

How then was the ability of society to reproduce itself agriculturally restored in the midst of the late-feudal crisis? As backwards as it may sound now, the answer is capitalist social relations. In the development of a mode of production based on the productivity of labor, European society found a system much more suited to the rapid appropriation of ecological surpluses. To Jason W. Moore,

Modernity’s law of value is an exceedingly peculiar way of organizing life. Born amid the rise of capitalism after 1450, the law of value enabled an unprecedented historical transition: from land productivity to labor productivity as the metric of wealth and power. It was an ingenious civilizational strategy, for it enabled the deployment of capitalist technics – crystalizations of tools and ideas, power and nature – to appropriate the wealth of uncommodified nature in service to advancing labor productivity.3

The ecological implications of this new set of relations was obvious immediately. Moore continues later,

The rise of capitalism after 1450 was made possible by an epochal shift in the scale, speed, and scope of landscape transformation in the Atlantic world and beyond…Feudal Europe had taken centuries to deforest large expanses of western and central Europe. After 1450, comparable deforestation occurred in decades, not centuries.4

Despite misconceptions of capitalism as a closed system that endlessly generates surplus through labor exploitation alone, it is structurally dependent on the continual appropriation of resources it neither reproduces nor accounts for within its own economic logic. This is most obvious in ecology, where capitalism has rapidly appropriated the “free gifts” of “nature” to fuel accumulation since its infancy. Consider fossil fuels, a non-renewable set of resources which formed over a very long period in very specific conditions several hundred million years ago. Oil, coal and natural gas jump-started capitalism via the industrial revolution and allowed staggering levels of accumulation. It remains a major question, however, whether capitalism can maintain adequate levels of accumulation once these appropriated energy sources dry up. The same applies to capitalism’s shifting relationship with reproductive labor over its history. Very early on, the cost of sustaining and reproducing the working class was covered in part by the state. At times, however, the state refuses to pay the full cost of social reproduction and simply allows proles to die faster than they reproduce. This was especially the case when Engels did his famous survey of the working class in England, finding poverty and suffering on a staggering scale in what was the most developed capitalist nation on earth.

Capitalists continually seek anything that will give them an advantage over their rivals. Aside from the classic economic way in which capitalists find this edge (the development of the productivity of labor), they will also “cheat” the system to push costs into other spheres. To Moore, this takes the form of what he calls the “Four Cheaps”, and it shows the intersection of the pure economic logic of capitalism, ecology and feminism.

The substance of value is socially necessary labor-time. The drive to advance labor productivity is fundamental to competitive fitness. This means that the exploitation of commodified labor-power is central to capital accumulation, and to the survival of individual capitalists. But this cannot be the end of the story. For the relations necessary to accumulate abstract social labor are—necessarily—more expansive, in scale, scope, speed, and intensity. Capital must not only ceaselessly accumulate and revolutionize commodity production; it must ceaselessly search for, and find ways to produce, Cheap Natures: a rising stream of low-cost food, labor-power, energy, and raw materials to the factory gates (or office doors, or…). These are the Four Cheaps. The law of value in capitalism is a law of Cheap Nature.5

In the case of agriculture, capitalism has been saved time and time again by its ability to produce cheap food. Cheap food, as defined by Moore, simply means more calories for less average labor-time. The incredibly fertile natural soils of the colonized American continents produced calories with few inputs once the free gifts of the European continent dried up. But this did not last particularly long, and faced with the loss of naturally rich soils, capitalism has been forced to artificially prop up soil and agricultural productivity in a number of ways. This brings us to the modern capitalist agricultural model we are all unfortunately familiar with. The next several sections will explore the ways in which this new agriculture functions, and why it is thoroughly unsustainable.

Why Capital Avoids Farms and Invests in Agriculture

It’s no secret that modern farming is a heavily subsidized industry. Subsidies to farmers tend to come in several forms, whether they be counter-cyclical payments, direct payments, disaster relief, or loans. The necessity for capitalist states to prop up some of the most vital sectors of the global economy should tell us something about capitalism. Indeed, what it tells us is that farming is not a particularly profitable sector of agriculture and all the appropriative tricks capital has pulled to try and make it a profitable sector are coming back around to potentially put the whole agricultural sector at risk of collapse.

To begin with, on-farm processes make up a small chunk of the total profitability of the agricultural sector. According to Lewontin and Levins,

The most striking change in the nature of agricultural production in the United States since the turn of the century is in the composition of inputs – the seed, fertilizer, energy, water, land and labor – used by the farmer in production…

The total value of inputs into farming rose from an index value of 85 in 1910 to about 100 in 1975 (1967 = 100), which is not a very great increase, but the nature of these inputs changed drastically. Inputs produced on the farm itself went from an index value of 175 down to 90 between 1910 and 1975, while the index value of inputs purchased from outside the farm rose from 38 to 105. That is, farmers used to grow their own seed, raise their own horses and mules, raise the hay the livestock ate, and spread manure from these animals on the land. Now farmers buy their seed from Pioneer Hybrid Seed Company, their “mules” from Ford Motor Company, the “hay” to feed those “mules” from Exxon, and the “manure” from Union Carbide. Thus farming has changed from a productive process, which originated most of its own inputs and converted them into outputs, to a process that passes materials and energy through from an external supplier to an external buyer.6 (emphasis our own)

They continue,

At present, only 10 percent of the value added in agriculture is actually added on the farm. About 40 percent of the value is added in creating inputs (fertilizer, machinery, seeds, hired labor, fuel, pesticides), after the farm commodities leave the farm gate. Another facet of this structure is that, although the percent of the labor force engaged in farming has dropped from 40 percent in 1900 to 4 percent in 1975…the number of those who supply, service, transport, transform, and produce farm inputs and farm outputs has grown; for every person working on the farm, there are now about six persons engaged in off-farm agricultural work. To sum up, farm production is now only a small fraction of agricultural production.7 (emphasis the author’s)

The point being that large scale capital flows into off-farm agricultural production and distribution, leaving the actual farming to petty capitalists constantly searching for cheap labor, cheap inputs and cheap solutions at the expense of workers and our ecology.

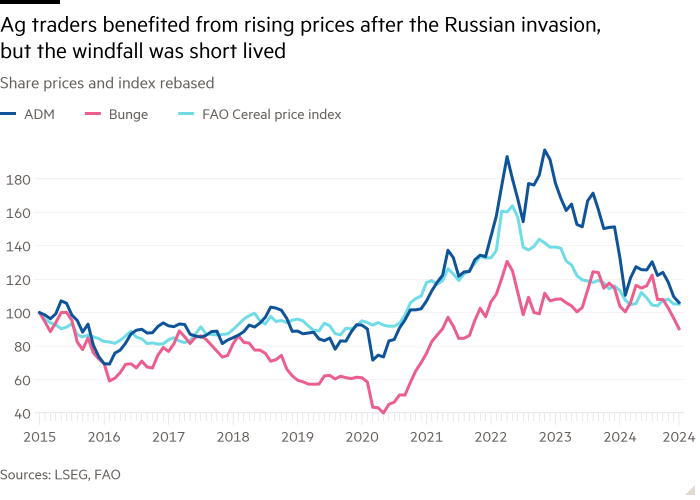

A concrete example of this system’s instability can be seen in the centralization of capital in capitalist agriculture around these off-farm sectors. Some of the largest names in the agricultural industry are the multinational giants collectively referred to as ABCD (Archer-Daniels-Midland, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus). These four corporations are primarily concerned not with crop production, but with commodity trading and food processing. They control roughly 70% of the global grain trade, have heavy stakes in palm oil trading and manufacturing as well as monopolies on various oilseed interests.8 However, they operate on razor-thin margins. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, for example, saw global grain prices skyrocket, before crashing again in 2024 (nothing like a bit of good old fashioned war-profiteering).9 During this crash, ADM and Bunge reported steep declines in their annual profits, down 48% and 49%, respectively. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, these war-driven price shocks took place with little regard for the real production and reserves of grain, which remained abundant throughout the market turmoil.10

While all of these corporations do own large tracts of land for direct crop production (Cargill, for example, owns two large palm plantations in Indonesia which account for 11% of the total value of the countries palm oil exports), the preferred model remains to avoid labor intensive on-farm agricultural processes, buying the products for processing and trading only after they have been harvested, pushing the high labor costs associated with crop production onto smallholding farmers.11

The lot of the smallholder in capitalism is a poor one, let’s not get it confused, but like all petty capitalists, they too are prone to reactionary practices in regards to labor and ecology. To Marx, the petty bourgeoisie was “…a transition class, in which the interests of two classes are simultaneously mutually blunted.”12 They protest the power of the large agricultural corporations, on whom they depend to buy their inputs and, in many cases, sell their outputs, while they simultaneously exploit cheap, often immigrant, labor and pollute their local environment using pesticides and synthetic fertilizers.

The search for efficiency in agriculture on both the large and small scale of capital has led to increasingly self-defeating practices. In many cases, seeds such as hybrid maize are engineered by large agricultural firms to produce exceptionally high yields, but the resulting crops are often intentionally incapable of producing viable seeds for future planting. Thus, every year farmers have to return to the company selling these seeds, instead of saving a small percentage of the harvest to plant the following season. Anyone who has a small garden and grows their plants from seed will be familiar with this process and will recognize the F1 label on most seed packets. F1 seeds are hybrids, made by crossing two seed lines to produce a plant with traits desirable to the average gardener – disease resistance, uniformity, picture perfect tomatoes, etc. However, because the plant is a hybrid (just like the maize grown by small farmers), if you save the seeds, they will either not grow at all or become a different plant than you originally grew, as the F1 seed you brought was produced by crossing two lines of parent plants. This is a microcosm of the larger agricultural industry, and why, if you can, you should grow heirloom crops, as they “grow true” and you can save the seeds for the next year.

Of course, the massive investment in off-farm agricultural industries was not the lone idea of some enlightened group of entrepreneurial capitalists. Chemical production, for example, ramped up massively in the United States via mass state spending during WWII, and afterwards, chemical manufacturers suddenly had a large amount of state of the art fixed capital at their disposal and utilized this with great effect in the production of synthetic fertilizers (discussed more in the next section) and pesticides.

Pesticides such as herbicides, fungicides and insecticides make up a large part of the modern agricultural system. They promise to raise productivity but have detrimental secondary effects, all of which are growing in consequence. They can be carcinogenic and have a tendency to seep into the water table and thus our water supply. There is simply no safe level of exposure to these chemicals – for the average person or for the farm laborers using them. Herbicides specifically are rapidly losing effectiveness, as “superweeds” outpace capitalist scientists who continually develop new chemicals to poison their fields only for the weeds to evolve resistance and continue to outcompete crops.

Post-WWII there was also another massive increase in on-farm labor productivity due in part to the rise of mechanization of certain planting and harvesting techniques. Partnered with the usage of hybrid seeds, synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, this new mechanization led to the advance of the petrochemical complex at the heart of modern agriculture.

All of this is to say that despite its historically unparalleled efficiency, this new system of agriculture based on a divide between on-farm and off-farm agricultural processes, as well as cheap chemical inputs, cheap energy and cheap labor, has run up against natural limits. Crucially, it has tested the limits of labor efficiency. According to Frank Bardacke,

Agriculture remains dependent on natural cycles and rhythms. Agribusiness cannot escape the seasons, unpredictable changes in the climate, and the natural tempo of individual plants, which do not mature at the same rate. It cannot escape mysterious differences in seed performance, or the interactions between water, sun, and soil, all of which make it relatively hard to mechanize agriculture, and virtually impossible to convert it into a kind of deskilled manufacturing process…

Each failed attempt has its own story. The strawberry machine bruised the berries. The asparagus machine couldn’t cut the shoots without destroying the ability of the bulb to generate more shoots for a later harvest. The celery machine couldn’t cut the stalks cleanly enough to be suitable for the fresh market. The lemon tree shaker produced three to seven times as much unmarketable fruit as did hand picking. Most other tree shakers do too much damage to the tree roots, although many nut trees can withstand the shaking. The one great mechanical success is the contraption that picks canning tomatoes, which, combined with a reengineered tomato, did replace thousands of workers. Otherwise, fresh tomatoes, like most other fruits and vegetables, are harvested by proficient workers making judgments and wielding tools.13

On-farm labor efficiency can only be pushed so far; machines for harvesting are only practical with specific crops, pesticides do not increase yields so much as protect already existing yields and soil health can only be pushed so far. What this means is that agriculture is fundamentally incompatible with the capitalist mode of production, both in a strict economic sense and an ecological one. As we will attempt to show in a later section, it is only in a classless society based on rational planning, free from the law of value, that solutions to these problems can be adequately addressed. But before we get to that, we need to take one last stop on our tour of capitalist agriculture to discuss one of the most important inputs to the agricultural process – synthetic fertilizers – to see the effect they have on the basis of all our lives, the soil.

The Nitrogen Cycle and Soil Erosion

One of the most important nutrients for plant life is nitrogen. It is one of the three primary nutrients used in synthetic fertilizers today, the others being phosphorus and potassium. Other nutrients such as sulfur, magnesium, and calcium are considered secondary inputs.

Nitrogen fertilizers use ammonia (NH3, a compound of nitrogen and hydrogen) as their starting point. Despite having a wide variety of industrial applications, over 70% of ammonia produced today is used to make synthetic fertilizers. The process of making ammonia is incredibly energy intensive, accounting for roughly 2% of total global energy consumption and 1.3% of CO2 emissions from the energy production system.14

With so much nitrogen in the air around us (roughly 78% of total atmospheric composition), it would seem odd that it’s necessary to produce nitrogen fertilizers to this degree, but atmospheric nitrogen cannot be used by crops in its raw form as N2. The natural process of converting this nitrogen into a useful form makes up part of the nitrogen cycle, whereby microbes in the soil form symbiotic relationships with certain plants to convert this atmospheric nitrogen into nitrates, nitrites and ammonia. Plants are able to easily absorb these forms of nitrogen, and certain species such as legumes have evolved to grow small nodules on their roots which act as habitats for these nitrogen fixing bacteria.

This all happens naturally, but only in healthy soil. Healthy soil maintains a rich balance of microbiotic life (bacteria, fungi, etc.) in an organic strata capable of supporting plant life. This delicate web of life is destroyed through over-tilling, over-grazing, a lack of crop variety and reliance on synthetic fertilizers.

Maintaining healthy soil is a process too labor and time intensive for capital to wait around for, so it’s much more profitable and efficient for capitalists to just pump dying soil full of synthetic fertilizers to mimic the outcomes of naturally healthy soil. The process of the degradation of healthy topsoils due to the loss of organic matter and nutrients, as well as the accumulation of pollutants, is called soil erosion, and it is one of the biggest problems we will face in our generation of capitalism. According to the UN,

Around 30% of the world’s soils are moderately to highly degraded. Forty percent of these degraded soils are located in Africa and most of the rest are in areas that are afflicted by poverty and food insecurity. It is estimated that at least 60% of the soils of the EU are affected by one or more degradational process.

Most future land degradation is predicted to occur in the areas with the largest amount of arable land remaining. If current trends continue, experts estimate that by 2050, more than 90% of the Earth’s land areas will be substantially degraded, 4 billion people will live in drylands, 50–700 million people will be forced to migrate, and global crop yields will be reduced by an average of 10% and up to 50% in some regions.15

The Agriculture of Tomorrow

If the proletariat thought it had enough on its hands with its historic mission to overthrow class society once and for all, well too bad, because it’s also going to have to figure out a way to produce and distribute enough food to keep the revolution going, before beginning a radical ecological overhaul of the entire agricultural megasystem. To push this movement forward an infinitesimally small amount, we will outline key considerations for socialist agriculture to ensure its long-term sustainability as a system.

Socialist Agriculture Defined

The model we’re going to put forward here for a socialist agriculture owes heavily to the field of study known as agroecology. Instead of being a step-by-step guide of How To Do Sustainable Agriculture TODAY Or Your Money Back!™, agroecology is a conceptual framework for viewing agricultural systems as ecological systems. Which, when you put it like that, they obviously are. Many sustainable agricultural models, however, are what we might call environmental as opposed to ecological. What’s the difference? To Murray Bookchin, environmentalism designates

…a mechanistic, instrumental outlook that sees nature as a passive habitat composed of “objects” such as animals, plants, minerals, and the like that must merely be rendered more serviceable for human use… Environmentalism tends to reduce nature to a storage bin of “natural resources” or “raw materials.” Within this context, very little of a social nature is spared from the environmentalist’s vocabulary: cities become “urban resources” and their inhabitants “human resources.” If the word resources leaps out so frequently from environmentalistic discussions of nature, cities, and people, an issue more important than mere word play is at stake. Environmentalism…tends to view the ecological project for attaining a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature as a truce rather than a lasting equilibrium. The “harmony” of the environmentalist centers around the development of new techniques for plundering the natural world with minimal disruption of the human “habitat.” Environmentalism does not question the most basic premise of the present society, notably, that humanity must dominate nature; rather, it seeks to facilitate that notion by developing techniques for diminishing the hazards caused by the reckless despoliation of the environment.16 (emphasis our own)

Put like this, the vast majority of the capitalist class could be called environmentalists. They seek greener ways to appropriate the “free gifts” of nature. More efficient ways of subjugating the natural world to capital. Ecology, on the other hand, begins by understanding that there is no natural system that we stand outside of. The labor process is a process of nature, and, viewed systemically, must see itself as such if the full implications of every change we make to the world around us are ever going to be accounted for.

So what does that mean for agriculture? It begins by understanding that agricultural systems are nested within broader ecological ones. It means that encouraging the variety of our local ecology (number of pollinators and pollinator friendly native plants, the extent of natural ecosystems like forests, kelp beds, meadowlands, and so on) is important for both moral and practical reasons. As we’ve seen in our brief tour of capitalist agriculture, privileging the “human” over the “natural” has led to a rapid decline in either set of systems to be able to support themselves. For our socialist agricultural systems to function, they need to work in tandem with the ecological systems they are embedded within, instead of simply abstracting away crucial differences in local ecology. This will have implications for not only the way we produce food, but how we live as well.

But crucially, all this does not mean letting every landscape and city revert to its “natural” state and making everyone become an-prim foragers. To reiterate, humans are just as much a part of the natural world as kangaroos or spruce trees, and so are our laboring activities. What is needed then, is less a project focused solely on minimizing our impact on the world, and more an approach aimed at understanding the myriad ways our actions interact with the web of relations in our ecology.

Agroecology in Practice

With all of that in mind, let’s begin taking a look at how this would concretely change our on- and off-farm practices.

Although agroecology is a conceptual framework, its ecological dictums can be teased out in a number of ways to find concrete rules for agriculture. For example, the paper An Agroecological Europe in 2050: Multifunctional Agriculture for Healthy Eating by Xavier Poux and Pierre-Marie Aubert (shortened hereafter to TYFA, for the Ten Years For Agroecology modelling exercise) lists several principles that “guide researchers, practitioners and social actors in the field of agroecology.” They are,

– Recycling biomass, optimising and closing nutrient cycles

– Improving soil condition, especially its organic matter content and biological activity

– Reducing dependence on external synthetic inputs

– Minimising resource losses (solar radiation, soil, water, air) by managing the micro-climate, increasing soil cover, harvesting rainwater, etc.

– Enhancing and preserving the genetic diversity of crops and livestock

– Strengthening positive interactions between the different elements of agro-ecosystems, by (re-)connecting crop and livestock production, designing agroforestry systems, using push-and-pull strategies for pest control

– Integrating biodiversity protection as an element of food production

– Integrating short- and long-term considerations into decision-making

– Aiming for optimum yields rather than maximum yields

– Promoting value and adaptability17

Again, these principles are stated by Poux, Aubert and their researchers as being situational for several reasons. Firstly, as stated before, the only real dictum of agroecology is to treat agricultural systems as ecological systems. Everything listed above is secondary to that. Secondly, when we begin to get into the specifics of applying these principles, it will be clear that these are meant for European climates, which is to say, predominantly temperate climates. The paper in question is written directly for European policymakers and farmers. A number of their principles can be applied to, say, a tropical agricultural system, but the specificities of those systems (reliance on rainy seasons, extended daylight hours, less temperature variance, lack of frost, etc.) will require a different concrete approach to farming techniques. But as stated previously, the abstract principles of agroecology still apply.

Transitioning away from synthetic inputs

As stated in the TYFA model, one of the main ways in which ecological agriculture will be achieved will be by slashing our reliance on inputs such as synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. To the greatest extent possible, we need farms to either produce their own inputs or find a way to produce agricultural outputs without them. We have seen the impact these inputs have on the supply chain, the farm and the environment, but it is clear that in capitalist agriculture, they are necessary.

So how can we do without them?

The answer lies in understanding why these inputs are so necessary to capitalist agriculture. Capitalist agriculture is based on concentration and mass intensification of the farming processes. Efficiency at all costs. When a local environment is given over entirely to, say, soybean or maize production, the ability of the “natural” system to protect itself against imbalances of pests or unwanted fungal outbreaks is massively curtailed. When it comes to pesticides, a nuanced approach will be needed to deal with pests and fungal disease outbreaks without resorting to mass poisonings. This approach will be specific to the crops being grown and the environment they are being grown in. But as a rule, healthy soil, with its high variety of microbes, fungal networks and organic material, protects against fungal infections in crops and harmful microbial or pest imbalances in the soil by maintaining a complex balance of life. Beneficial insects such as certain types of wasps can also be encouraged in agroecological landscapes to balance insects currently considered pests either by hunting them or competing with them. Leaving space for “non-agricultural” ecological infrastructure networks to encourage these species will be vital.

Likewise, doing without herbicides is relatively simple; it requires higher labor inputs to weed and maintain healthy beds. This is a key element of truly sustainable agriculture, and is why such a system remains unattainable under capitalism. Envisioning a decline in labor productivity across an entire sector is only plausible within the context of a planned society. Capitalism functions without true planning because producers are constrained by the law of value, which compels them to produce as efficiently as possible. Anyone who forgoes the law eventually will go out of business.

So on one hand, we know that only a classless society can deliver global food security, but on the other, we can see that the age-old promise of communism – a massively efficient society where we all work as little as possible – is actually at odds with producing food ecologically. If we want to produce food in an agroecological fashion, labor inputs will have to rise, not fall. Any functioning political economy for communism will have to take this into account. Speaking philosophically, we believe that this will actually help hasten the onset of high communism – that state of affairs defined by Marx when “…the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to their ability, to each according to their needs!”.18 Capitalism has a way of obscuring what it is that we all are doing when we get up and go to work in the morning. Namely, that we are collectively reproducing society together. It does this through a mix of competition between workers, indirectly social labor, commodity fetishism and production for exchange. Under communism, however, it will be immediately apparent that the work you undertake contributes to a society that you recognize and had a hand in designing. There is no more fulfilling work in this sense than agricultural labor which, though it can be a massive pain in the ass at times, makes it directly clear how the labor process interacts with our broader ecology to facilitate the flourishing of human society.

This takes us (in a roundabout way) to synthetic fertilizers, which is a much more complicated problem. In the early stages of the transition to agroecological communism, we will simply have to do with as little of these fertilizers as possible, with the aim of completely doing away with them after a period of adjustment.19 There are a number of ways in which these inputs can be minimized. To begin, we must first recognize that when we talk about growing healthy crops, what we are primarily talking about is maintaining healthy soil. So firstly, we must consider no-till and permanent bed systems for many types of non-cereal crops. Capitalist fields are massively over-tilled. This is because it is easiest and cheapest to simply dig organic material such as manure into the soil with heavy machinery to make it break down faster. This tilling breaks up the complex webs of life within the soil that sustain crops throughout their lifecycles. Healthy, beneficial fungal networks and other microbial life are incredibly fragile, and any disturbance to them can be harmful to their ability to symbiotically grow with crops. No-till or minimal till farming practices get around this problem by consistently feeding the soil with a layer of organic material (usually compost and manure) over the top of the soil before planting directly into this top layer. This preserves the thriving life of the soil which in turn creates a healthy basis of nutrients for the crops to grow.

Additionally, when fields lay fallow, the web of life of the soil does not thrive nearly as much as when a healthy cropping system is in place. Weather such as rain and wind can also lead to a loss of topsoil and nutrients when nothing is growing. To combat this, beneficial cover crops can be used to stop soil erosion and actually encourage healthier soil by maintaining the nitrogen cycle, sequestering CO2 and keeping the structure of the soil in place to avoid topsoil loss. Legumes, for example, are excellent at fixing nitrogen, and a number of different varieties exist that can be grown alongside other crops as part of intercropping systems or consumed in their own right.

This type of farming (and specifically this type of soil maintenance) can be compared to the concept of black boxing in systems theory. There are entirely too many different forms of life that are constantly changing and interacting in just a single small bed of soil to ever truly map out their relationships to the crops being grown. What is needed, then, is a system of best practices where we measure inputs to the soil and what our results from each practice, constantly encouraging the web of life by replacing the organic substrate of the soil with decayed matter in the form of compost and manure. Clearly, however, different plants require different soil states, as requirements for PH level, water retention, nutrition levels, etc. will vary between each crop.

The issue with no or minimal till farming then becomes the need for large amounts of this compost and manure and, in an age where livestock rearing and crop production has been nearly completely decoupled, this can be quite hard to do. To make this change work, we would need large scale composting facilities that recycle food waste and agricultural detritus back into the agroecological system. In terms of manure, it would be necessary to reintroduce livestock into the crop production process. Poultry should be raised locally to crop production, and these birds could not only provide much needed manure for the farms but also consume unwanted pests in some fields (depending on the crops). But a major source of manure in this system would necessarily come from cattle and other ruminants, which brings us to the question many so-called “sustainable agricultural systems” fail to adequately answer: how can we maintain large scale cereal production without eroding our soils?

Diversification of Cropping Systems

Cereal production yields have grown very quickly under capitalism, specifically in the last century as the previously described systems of mechanization and intensification have led to a boom in productivity. Now, however, the overall productivity of grain farming has stagnated, as farmers are facing the realities of soil erosion, pesticide resistance and pollution.

Any serious ecological agricultural model will include some level of plant diversification in its cropping systems. Diversification has wide ranging benefits specific to the crops grown, but general advantages include encouraging symbiotic relationships among species, healthier soil and pest management. We briefly touched on cover cropping systems and the ability for some of these plants to be grown alongside other crops to encourage nitrogen fixation and avoid soil erosion, but ley farming takes this idea further. The basic idea behind ley systems is getting rid of permanent pastures for ruminants like cattle in favor of temporary pastures that are integrated into cropping systems. These temporary pastures are made up of ecologically beneficial local variants of grasses, legumes and certain types of forbs20, which both encourage high levels of biodiversity and promote healthy soil underfoot (or underhoof). Introducing these diverse pastures into crop rotations helps manage pests as, according to a study in the journal Agronomy for Sustainable Development,

…diversification is a key component of agroecological pest management. Diversification in time allows farmers to alternate (i) host and non-host crop species, thus reducing pest survival, and (ii) growing seasons, potentially exposing pests to unfavorable growth conditions. Diversification in space allows farmers to alternate host and non-host crop species within a field, thus reducing pests’ ability to find suitable hosts or environments.21

Sheep or goats can also follow cattle in the field rotations to further disrupt parasite cycles. Additionally, the manure created in the process of raising livestock is obviously beneficial to the cropping systems. To the greatest extent possible, these systems will close nutrient loops, recycling not just animal waste but crop detritus to sequester carbon and save the nutrients for later crops through types of composting.

This gets us to a crucial distinction between the types of livestock raised: ruminants and monogastrics. Ruminants are animals like cattle and sheep who, due to their ability to ferment plant matter in their specialized digestive tracts with multiple stomachs, are able to live off simple plant matter like grasses. The term monogastric is a bit of a catch all, but it refers to animals like humans, pigs and poultry who have one stomach and are unable to draw the necessary nutrients from, say, grasses, the way ruminants do. Because of this, monogastric livestock require feed from other sources, namely cereals and oilseeds, which puts them in direct competition for food with humans. But capitalism loves these animals because some of them are easily adapted to efficient, intensive production. The lives of chickens, for example, are easily adapted to the factory system – they’re kept in crowded indoor environments with several thousand to a barn, they can be selectively bred to encourage rapid growth and they can be fed cheap feed, slaughtered and processed with mechanical ease. This is done always with the aim of cutting down the turnaround time for a filet or a thigh, and “…transforming poultry raising into a streamlined industrial process more closely resembling chemical manufacture than traditional agriculture.”22 The implications of these factory farming techniques – ranging from the diminished quality of poultry, to the short, terrible lives of the birds, to the heavy use of chemical inputs and, of course, the creation of ideal conditions for the incubation of pandemics – are all secondary to profitability.

The suitability of certain types of these monogastrics to capitalist production means that more and more land has been given over to the production of cereals and oilseeds to feed these animals, and not humans. According to the TYFA model, 60% of cereals and 70% of oilseeds available in the European continent are used to feed livestock. What this implies is that utilizing the abilities of ruminants to enhance the biodiversity of temporary and (to a lesser degree) permanent grasslands is much more valid and useful in an agroecological system than raising as many monogastric animals. Regarding ruminant herbivore systems in the TYFA model,

They all maximise the use of extensive grasslands in line with an approach based on non-competition between animal feed and human food. The efficiency of these systems is low if we just look at energy (the conversion of solar energy into plant then animal biomass), but it becomes high if we consider that they make use of what humans cannot eat. The extensive grassland approach implies changing breeds and performance criteria. Physical productivity (the quantity of meat or milk per animal) becomes secondary, in favour of criteria such as hardiness and the ability to eat fodder resources containing more woody species that are available over a longer period. In some cases, herd management may imply grazing animals learning to valorize semi-natural ecosystems.23 (emphasis ours)

Whether or not a local commune or city or whatever feels the need to consume animal products in their diets (we still hold out the possibility of some sort of vegan utopian commune like we pictured when we were teenagers listening to Earth Crisis and reading Murray Bookchin), livestock remain useful, and there is no reason at all to expect communist society to treat them the same hideous way capitalist society does. As long as the rearing of livestock follows agroecological lines, prioritizing the roles played by each animal in the broader ecological systems, we will not have to assume a complete abandoning of meat and dairy. Livestock may prove vital to functioning agroecological systems, not only by nourishing our diets but also by sustaining ecological systems such as meadowlands.

Beyond what we’ve briefly discussed here, namely preliminary approaches to transitioning away from synthetic inputs, improving the condition of the soil, diversifying cropping systems and a decrease in agricultural labor productivity, there are a large number of other, less abstract problems to be solved in a socialist agroecological system. These include on-farm questions such as the localized requirements of crops from perennials to annuals/biannuals, more specific crop rotations and disease prevention techniques, to the preservation and preparing of food as well as efficient produce transportation systems.

But even these additional questions are just a small part of the much larger system of socialist planning, and cannot be taken in isolation. When we defined agriculture at the beginning of this essay, we mentioned that if we only looked at the on-farm practices of agriculture, we would lose sight of the bigger picture. To take that a step further and paraphrase a well-known quote, when we pick out any single system on its own, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe. Socialist agricultural planning necessarily includes energy, housing and transportation planning. It includes what we eat and who we eat it with. It includes social reproduction and the hefty decisions of what we are working towards as a society. Our point being, anyone involved in socialist agricultural research must necessarily be in conversation researchers from every other sector of the planning field.

What Must Change

The danger of discussing any kind of model, especially one predicated on a classless society, is that we tend to assume a linear leap to a time and place where the model can be implemented. For our purposes, we assumed that a classless society capable of rational planning and coordination had just sort of sprung into existence in all places at once.

As revolutionary socialists, communists and anarchists, we all make this mistake intentionally because a transitional revolutionary period is much more dangerous and chaotic than we give it credit for. We romanticize revolutions because their reality is so violent that it’s better to have a strategy that involves riling people up for revolution, having a plan for what we do after we get power and just hoping for the best between now and then. This is also the answer to why proles don’t just rebel for communism today. Ideological indoctrination aside, very few proles are actually against the ideas of a classless society. It would be in all of our best interests to just do communism now. But it is very much not in any prole’s interest to actually go through with the system shattering act of carrying out a revolution.

And this is why, if any of us are still serious and committed to the idea of revolutionary politics, we need to be honest with ourselves. The goal of us lefties can’t just be to agitate, organize and educate. It needs to be to plan communist systems in advance, both to implement in the early stages of communism and during the tumultuous revolutionary period. It’s worth pointing out that these will be a very different set of systems, and that, however much we might want the revolution to be a short bump on the path of human development, it might be an extended and constantly evolving period. Planning literature needs to take both of these periods into account, with the hope that revolutionary planning will ease us nicely into status-quo communist planning.24

So how do we apply these ideas to agroecology? The first thing to consider, and something we probably should have brought up earlier, is that agroecology requires much more practice to get a sense of its possibilities. For example, in the TYFA model, estimates for future yields are left conservative as the authors of the paper consider agroecology an “innovation pathway” which, once adopted on a large scale, will lead to compounding innovations. This might sound like a copout, but the logic is sound. The development of the general intellect in society is a crucial factor for other forms of innovation: indirectly in capitalism, directly in communism. Once society collectively is able to drive innovation not for maximum efficiency but for ecological utility and variety, there would be no reason to suspect innovation would halt. Agroecology is a hard thing to practice under capitalism – partly because it’s necessary to practice at scale to get a sense of its full capabilities, and partly because this type of lower-efficiency agriculture is not rewarded in the competitive commodity economy.

But this is exactly why it’s necessary to attempt as much of this innovation now as possible. The period of mass revolutionary turmoil needs to be kept as short as possible, especially when it comes to the question of producing food. How this is done prior to a revolution is a large question, with answers ranging from worker’s coops to mass party led investment into agricultural research to individuals to groups with access to small plots of land experimenting with cultivars, yields and other processes. As utopian as it sounds, proles organizing pockets of agricultural production under capitalism may just be a prerequisite for a successful revolution. To speak in truisms, a revolution that can’t adequately supply its people won’t be supplied for very long. And what sounds more utopian? A mass, sudden seizing of the agricultural means of production without major disruption to the food supply, or the development of independent agricultural networks before the period of upheaval? Our point being, the latter, however possible it may be, would seem to be a necessity in one form or another for the revolution to succeed. This is especially true as capitalism enters its death throes and its ability to supply food dwindles – at times slowly and at times abruptly.

Strategies for preparation like this always seem to fall victim to a kind of collapse fetishizing accelerationism. There’s obviously a real danger to this since rumors of capitalism’s demise have long been greatly overstated. Until the thing topples over once and for all, it’s best to assume things are going to get just slightly worse everyday until there’s some system shock like the collapse of the FIRE sectors due to climate chaos, a large war, or some other event that would be hard to accurately predict. Leave the apocalypse predictions to the millenarians. When organizing around strategies of preparation, you need to orient yourself properly, by which we mean less around predictions and guesses and more around concrete situations currently in existence. The Black Panthers enjoyed success partly due to their ability to look around American inner-cities, accurately diagnose the needs of the black prole population and act accordingly. Kids weren’t getting enough nutrition before and during school, so the Panthers stepped in to offer free breakfasts for schoolchildren, building concrete support for a project aimed at overthrowing the white supremacist American state.

The TYFA model hints at one such need currently going unfulfilled which is the need for abundant, healthy food. The model, based on a 10-year mass restructuring of Europe’s agricultural production and imports, sees a decline in overall production due to a sharp cut in imports.25 Part of the way the model retains the ability to feed the continent’s population in spite of this production decline is through a change in society-wide diets. The diet suggested by the authors

…contains fewer animal products (but those consumed are of better quality) and less sugar; on the other hand, it is higher in fibre and contains more—seasonal—fruit and vegetables. Overall, it is more nutritionally balanced and has absolute environmental quality if we consider the replacement of pesticides by beneficial organisms.26

The upshot being that modern diets in Europe and elsewhere in the imperial core are excessively unbalanced and unhealthy. In states that are peripheral to the imperial core things are much the same, but there is obviously a much larger strata of society in these states that simply does not have enough to eat, healthy or otherwise. As we’ve repeated time and time again in this essay, organizing a society around maximum efficiency necessarily clashes with our ability to grow food. What is urgently needed now is for socialist movements to pioneer agroecological systems, proving in practice that global food security can only be achieved through a classless society. How likely this is to happen depends to a certain extent on our own efforts. Today’s struggles for a classless society are unique in that if they fail, they may not simply open the door to another century of capitalism. A failure today, in the face of the global climate and biodiversity crises, will be much more ruinous.

Footnotes

- Why the focus solely on Western European feudalism? Because this was the set of systems that led directly to capitalism. Other systems were perhaps headed in that direction, including feudal Japan, but for a variety of reasons they never fully adopted private property as the basis of all production. Once developed in Western Europe, capitalist production was violently exported to the rest of the world. ↩︎

- Perry Anderson (1974). Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism. ↩︎

- Jason W. Moore (2015). Capitalism in the Web of Life. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Richard Levins and Richard Lewontin (1985). The Dialectical Biologist. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Sophia Murphy, David Burch and Jennifer Clapp (2012). “Cereal Secrets: The world’s largest commodity traders and global trends in agriculture”, Oxfam Reports. ↩︎

- Susannah Savage (2025). “‘ABCD’ agricultural traders struggle to escape boom-bust cycle”, Financial Times. Online: https://www.ft.com/content/e8d6be6e-c7a9-496f-b4e2-d9916b9d80dc ↩︎

- Pat Mooney (2022). “The grain giants have made a bonanza from hunger. Time to take them apart”, openDemocracy. Online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/abcd-grain-giants-profit-world-hunger/ ↩︎

- Sophia Murphy, David Burch and Jennifer Clapp (2012). “Cereal Secrets: The world’s largest commodity traders and global trends in agriculture”, Oxfam Reports. ↩︎

- Karl Marx (1854). The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. ↩︎

- Frank Bardacke (2011). Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers. ↩︎

- “Ammonia Technology Roadmap: Towards more sustainable nitrogen fertiliser production” (2021). International Energy Agency. Online:

https://www.iea.org/reports/ammonia-technology-roadmap ↩︎ - “Soil Degradation” (2024). United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Online:

https://www.undrr.org/understanding-disaster-risk/terminology/hips/gh0402 ↩︎ - Murray Bookchin (1982). The Ecology of Freedom. ↩︎

- Xavier Poux and Pierre-Marie Aubert (2018). “An agroecological Europe in 2050: multifunctional agriculture for healthy eating: Findings from the Ten Years For Agroecology (TYFA) modelling exercise”. ↩︎

- Karl Marx (1875). Critique of the Gotha Program. ↩︎

- Nitrogen fertilizers will need to be used as a stand-by for as long as it takes society to develop meaningful processes for closing the nitrogen loop in agriculture. Fertilizers for elements such as phosphorus, however, are a different story. While much can be done to avoid the soil leaching its phosphorus content, it may be that an amount of phosphorus mining will always be necessary. At this stage, it is difficult to say. ↩︎

- Forbs are simply broadleaf, herbaceous plants. They differ from grasses in that their roots tend to be deeper than the shallow roots of grasses, and are thus able to pull nutrients from deeper in the soil. A mix of grasses and forbs that are edible to livestock are thus mutually beneficial to the livestock and the ecology of the meadowlands. ↩︎

- Guillaume Martin, et al. (2020). “Role of ley pastures in tomorrow’s cropping systems. A review”, Agronomy for Sustainable Development. ↩︎

- Mike Davis (2005). The Monster At Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu. ↩︎

- Xavier Poux and Pierre-Marie Aubert (2018). “An agroecological Europe in 2050: multifunctional agriculture for healthy eating: Findings from the Ten Years For Agroecology (TYFA) modelling exercise”. ↩︎

- If we wanted to further periodize socialist planning, we might say that the first stage will be revolutionary planning, when the chaos of the struggle over the entire capitalist productive apparatus will be the determining factor in planning. The second would be a period of formal subsumption, when planning must make do with the productive forces left to us from capitalism. The determining factor in this stage of planning will be overhauling the capitalist productive forces to force them to better fit communal property relations, and will include climate disaster planning and the remodeling of the way we labor. Finally, the third period will be what we called communist “status-quo” planning, when the last vestiges of capitalism have gone from our lives (in its infrastructure and philosophies) and we are able to plan a really subsumed communist society. Each stage of planning will require a completely different orientation and structure. ↩︎

- Besides encouraging local food sovereignty, the cut in imports in the TYFA model are mainly the result of halting feed imports for livestock from the Americas. ↩︎

- Xavier Poux and Pierre-Marie Aubert (2018). “An agroecological Europe in 2050: multifunctional agriculture for healthy eating: Findings from the Ten Years For Agroecology (TYFA) modelling exercise”. ↩︎